Growing up in Angoche, a coastal city in northern Mozambique, Rare Pride Campaign Manager Isidro Intave saw the nearby beach and mangrove banks as sources of never-ending play and possibility. Isidro and his friends spent the bulk of their childhood knee-deep in those ecosystems, where they swam, fished, gleaned mussels and scavenged the shore for things they could repurpose. He’d come home with fruits he’d picked from trees and turn them into tires for his wooden toy cars. “My friends and I, we had a lot of fun,” says Isidro. “We used to play in the sea, building boats using parts of a banana tree, turning plastic containers into floaters. We used palm trees to make a mini sailboat.”

It felt like easy and harmless fun, carried out on the assumption that Angoche’s coastal habitats could serve as Isidro’s lush playgrounds forever. “I did not understand at the time, the importance of natural resources,” he says.

As part of the coastal fishery, the brimming waters and miles of mangroves offered another, more tangible gift to the rest of the community: a stable source of livelihood and food. Back then, Angoche and other coastal communities could rely on (relatively) plenty of coastal fish stocks to provide them with most of their dietary protein — while feeding many inland Mozambicans as well — and keep them employed as small-scale fishers, seafood processors, and more. But that sense of security in fishing is gone.

While coastal people still depend heavily on small-scale fishing — a form of coastal fishing that mostly feeds locals, uses basic gear, and often lacks the resources for a motorized boat — the sector is now shrouded in uncertainty. According to a 2010 study of the country’s small-scale fisheries catch in the African Journal of Marine Science, catch peaked in the mid-1980s and steadily declined thereafter. Isidro spent 20 years in the thick of it, watching decline take over fisheries in big cities and small towns alike and combatting it as a fisheries extensionist and provincial delegate for the National Institute for the Development of Small-Scale Fisheries and Aquaculture (IDEPA).

While coastal people still depend heavily on small-scale fishing — a form of coastal fishing that mostly feeds locals, uses basic gear, and often lacks the resources for a motorized boat — the sector is now shrouded in uncertainty. According to a 2010 study of the country’s small-scale fisheries catch in the African Journal of Marine Science, catch peaked in the mid-1980s and steadily declined thereafter. Isidro spent 20 years in the thick of it, watching decline take over fisheries in big cities and small towns alike and combatting it as a fisheries extensionist and provincial delegate for the National Institute for the Development of Small-Scale Fisheries and Aquaculture (IDEPA).

Population growth and the accompanying rise in fishers have perpetuated the decline, mainly by causing increasingly competitive fishers to resort to overfishing and unsustainable fishing. In Mozambique, the latter takes forms like beach seining and small-gauge nets. At the same time, companies and individuals have taken part in gas and oil drilling, coastal development, and tourism, which can wipe out ecosystems like mangroves, coral reefs and seagrass beds, where fish populations breed and live. Climate change compounds human impact on the environment, worsening the effects of natural disasters like cyclones and floods on Mozambique’s exposed coastline.

As an IDEPA agent, Isidro trained local people in techniques to reduce their ecological impact. “I played a role in the education and awareness of fishing communities to preserve the fishery’s resources and the oceans in general, including mangrove planting and preservation of endangered species, such as sea turtles and seagulls,” he says.

Though his work helped boost awareness of better ways to interact with the environment, it came in small doses. The IDEPA, Isidro and other staffers were dealing with pervasive overfishing and illegal fishing practices that had evolved into habit. They realized that they needed to begin to exploring transformative, long-term options for sustainable fishing that could eventually serve as the entire country’s new fishing scheme.

Last year, with support from the Nordic Development Fund and the World Bank, the IDEPA partnered with Rare to pilot a sustainable fishing program in six sites on the southern and northern coasts of Mozambique. Their goal: to show fishers why and how to press pause on marine resource use and extraction without sacrificing their means of supporting themselves and their families.

The IDEPA assigned Isidro and five other Rare Pride Campaign Managers selected from within its ranks to lead campaigns promoting the adoption of “TURF+Reserves,” a community-driven, rights-based fisheries management strategy that the IDEPA is eyeing for potential application to fishing on the whole coast. In part, the government will make that decision based on how well the strategy serves the pilot sites, which from south to north include Matutuíne, Inharrime, Massinga, Inharasso, Memba and Mefunvo.

One of the toughest and most important steps to seeing a TURF+Reserve put in place and producing local environmental and economic benefits is getting the community to support the concept of it in the first place. The Pride campaigns create local buy-in for the approach by using behavioral design principles (like the human tendency to make decisions not only based on rationality, but also on emotions) to guide engagement and inspire whole communities to adopt sustainable behaviors.

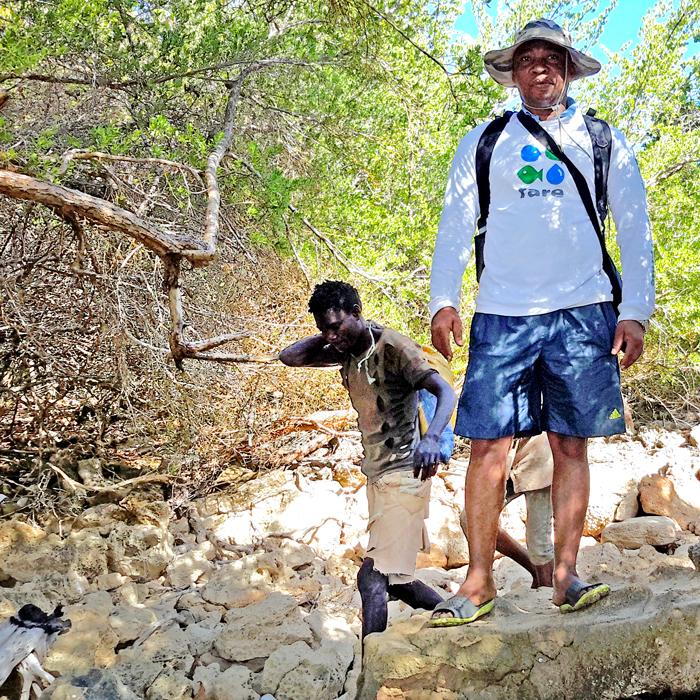

Isidro has spent the last year working with the Mefunvo Island community in the north. Though it’s not Isidro’s first effort to convert unsustainable fishing behavior, it is the first time he’s been equipped with Rare’s behavioral insights and a scientifically-backed solution that equally prioritizes fisheries sustainability and local fishing livelihoods. Making use of these tools, he’s seen a community of fishers, once stiffly resistant to change, accept their fishery’s limits and seek his help protecting their marine resources.

• • •

Mefunvo Island is one of 32 islands within the Quirimbas archipelago, much of which is encompassed by the Quirimbas National Park in northern Mozambique. Its fishers rely on species of fish, mollusks and crustaceans like the emperor, parrotfish, cockle and oyster. They’ve noticed a fall in stocks while out on the water, says Isidro. “According to the knowledge of the local fishermen, the current state of the small-scale fishery is bad and very low, comparing with 10 years ago,” he says.

Isidro surveyed the community to find out more about the fishery’s state. After speaking with fishers and other people in Mefunvo, he learned about the many forms of misuse taking place: local and migrant fishers were operating in large numbers within a single zone, fishing at all tides with no rest periods, using noxious or illegal gear like mosquito nets, destroying corals and mangroves, and catching protected species like sea turtles. Development activity worsened the impact — in Mefunvo, the use of toxic plants in the fishing grounds was an ongoing problem, says Isidro.

With this knowledge in hand, Isidro directed the campaign to inform people of the delicate balance of life in marine ecosystems and its role in stabilizing future fisheries productivity, as well as show them the effects of common misuse of the fishery. Many fishers acknowledged seeing the issues, but expressed concerned when Isidro then proposed his solution, the creation of a TURF+Reserve to manage Mefunvo’s fishery.

I have been humble, created friendships, respected local customs, and involved all layers of society in the activities of the campaign.

Isidro Intave, Rare Pride Campaign Manager, Mozambique

He learned that local fishers were hesitant about any effort that involved restricting use of their waters for conservation, as their only recent exposure to such an effort became associated with less room to fish and more room for abuse of power. “At the beginning of my campaign, the Mefunvo community showed resistance,” says Isidro. “They wanted no activity of reserves or sanctuaries in their community, noting that other islands, such as Quilalea and Quirimbas, had similar activities, and that these activities only benefited the park’s rangers. According to them, fishermen bribed the rangers, baptizing the areas as ‘reserves of corruption.’”

But Isidro had a more comprehensive solution for managing fisheries in mind. TURF+Reserves (short for territorial user rights for fishing + marine reserves) don’t rely solely on restricting fishing to give fish stocks and ecosystems the chance to recover. Instead, the approach pairs reserves with TURFs, zones of exclusive fishing access for local fishers. TURFS allow local fishers to fish in designated sections of their coastal waters without as much competition from outsiders or tons of overlap in a single fishing area.

In turn, pairing reserves with TURFs can prevent their abuse. When implemented in Rare sites, TURF areas are positioned in or near reserves, so the more local fishers heed and enforce reserve protections, the more potential they’ll see for recovered fish stocks to spill over into their TURF areas.

The TURF+Reserves concept was alien to the Mefunvo community, as Mozambique has historically had open-access fisheries. Open-access fishing has been part of the now national overfishing problem, by allowing for unrestricted use by fishers from near and far. When migrant fishers travel to other fisheries and use them, they create added pressure for local fishers already competing with one another in a shared space. TURF+Reserves have the potential to cut out the “tragedy of the commons” theory that researchers ascribe to open access by organizing and localizing use of strategically delineated fishing grounds.

Isidro went to work to show fishers how TURF+Reserves could bring the community both environmental and economic stability. Using the approach, communities could prioritize their local fishers in allocating the fishery’s use, while giving fish stocks and ecosystems under reserve protection room to bounce back. “I showed the advantages of having a TURF+Reserve, that this could help improve their fishing production and in a way improve the conditions of their lives and the community generally,” says Isidro. “I used the example of positive experiences of the strategy in countries such as Kenya, the Philippines, Italy, the Red Sea and Canada, among other places,” he says.

I showed the advantages of having a TURF+Reserve, that this could help improve their fishing production and in a way improve the conditions of their lives and the community generally.

Isidro Intave, Rare Pride Campaign Manager, Mozambique

Among those advantages is the strategy’s potential to help communities skillfully respond to challenges like climate change: by organizing around sustainable management and protecting critical ecosystems like mangroves and reefs within fisheries, communities can become more socially cohesive and boost their areas’ natural physical resilience to natural disasters.

Building trust was as important to Isidro as providing information, he says. Throughout the year, he had open, honest conversations with community members. “I have been humble to them, created friendships, respected local customs, and involved all layers of society in the activities of the campaign,” he says. “I had to be very determined in my work.”

Isidro’s candid conversations with members of the Mefunvo community helped him tackle remaining issues that affected their ability to unite around a management scheme. He found out, for instance, that their existing tool for collective management, their CCP (community fishing council), was uncoordinated. CCPs, the existing councils through which fishing communities organize in Mozambique, aren’t always in active use in Mozambican communities. Part of Rare and the IDEPA’s nationwide vision for small-scale fishing is empowering CCPs to become cohesive, well-organized groups through which communities carry out sustainable management. Isidro has worked with CCP members to better organize group discussion and fishery decision-making.

Ultimately, Isidro didn’t have to coax the community to embrace the concept of a TURF+Reserve. He laid out the realities, showed people how unsustainable fishing could affect their future and that of their family, and trusted them to make their own decisions. And it worked: fishers recently got together and acknowledged the impact of overfishing — particularly their concern about migrant fishermen sapping the stocks, says Isidro.

They approached Isidro with a request for help starting up the reserve element of the approach. “The fishermen have surprised me with a request to make a reserve on their island,” he says. “They are asking for 30 buoys and other material to demarcate and put a sign in the area of jurisdiction of the island, they want to develop a series of rules for fishing.” Now, Isidro, fishers and other community members with a stake in fishing are looking at first steps for design and implementation of a TURF+Reserve.

Mefunvo’s newfound momentum is exciting for Isidro, not only because it brings the possibility for finding a local — and even national — strategy for sustainable fishing in his country, but also because he recognizes the difficulty of the Mefunvo fishers’ decision to stop in their tracks, acknowledge a damaging dynamic taking place in the fishery, and step up to change it. “The willingness of CCP members and community leaders to create a community management and resource recovery area [TURF+Reserve] after our interpersonal contact leaves me with great hope that this community can change and preserve its resources,” he says.